☎️ Tell Tillis to Support Martin Nomination! ☎️

Representative Kidwell Speaks in Favor of Permitless Carry, HB 5

NC Speaker to Accept ‘Constitutional’ Carry Petitions

Urgent Message from Representative Keith Kidwell

GRNC News Update – January 2025

Join us at GRNC’s annual meeting on Saturday, 12/7 and meet US Senator Ted Budd!

Ready to renew your NC CHP?

Click here for important information

| Coming soon to the US Supreme Court: Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo |

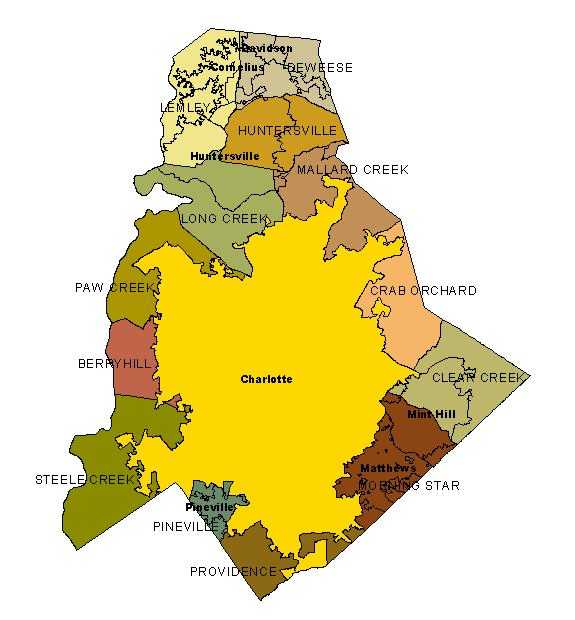

Read the LatestMecklenburg County Lawsuit |

|

|

| GRNC President Paul Valone congratulates incoming NC Supreme Court Associate Justice Richard Dietz at reception following Supreme Court investiture ceremony. In a clean sweep of judicial victories for the NC Supreme Court and NC Court of Appeals, the GRNC Political Victory Fund was central to electing Justice Dietz and securing conservative control of the Court. |

|

| GRNC President Paul Valone congratulates incoming NC Supreme Court Associate Justice Trey Allen at reception following Supreme Court investiture ceremony. In a clean sweep of judicial victories for the NC Supreme Court and NC Court of Appeals, the GRNC Political Victory Fund was central to electing Justice Allen and securing conservative control of the Court. |

| Have you stopped receiving GRNC email? |

|

GRNC Gun Permit Victory in Mecklenburg Sheriff McFadden now under court order to comply with gun permit laws

|

GRNC & GOA win preliminary injunction

against Mecklenburg County NC Sheriff

Click to hear HB398 audio